Archive: Views of a Dark World

We are too reliant on black swans to illuminate the unseen infrastructure on which we depend.

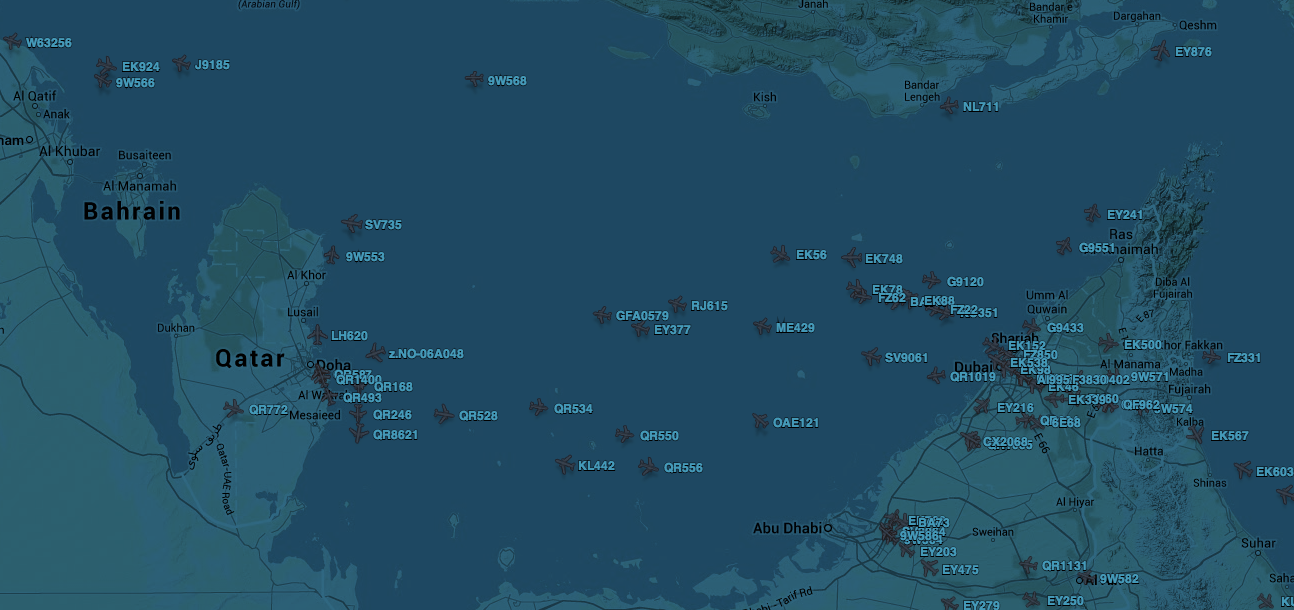

Flights pass through air traffic corridors between Doha and Dubai.

For a global society highly dependent on complex technical, economic and political systems, we manage to carry on our daily routines largely unaware of the hard and soft infrastructure—from pipes to policies—on which these systems rest. That is, until unexpected events, so-called black swans, illuminate the previously hidden pieces and surprise or unsettle us by their presence and function.

Take, for example, a recall of tainted food. Most of us feed ourselves largely unaware of the often intentionally cloaked pathways by which our food travels to us. When people fall ill and relevant supply chains are traced, we often see for the first time the mega-distributor that funnels carcasses from the far edges of the food network to our local market, via a few grinders, mixers and the odd mechanical recovery device or extruder. Sometimes we find that what we bought isn’t remotely what we expected. In the process, of finding out about failures in the system, we might get a glimpse of the farms, trucks, warehouses and machines that sit between the farm and our fridge.

Submarine cable map from Telegeography

More surprising still are the rare but spectacular outbreaks of transparency that come from corporate or government leaks. Edward Snowden’s continuing revelations about the activities of the global intelligence communities have shone a light on so-called deep state programs that collect massive amounts of communications data, and also point to the terrestrial, airborne and subsea infrastructures they tap. Network engineers, business analysts and telecom executives know these structures are there, but the general public was, until recently, largely unaware of how their Netflix accounts work, where their phone call activity is stored, or how their e-mail is delivered. Many remain so.

Russia’s sudden grab for the Crimea and possibly more of the Ukraine also has its own infrastructure feature: natural gas pipelines. Faster than you could say “Yanukovich,” maps of Ukraine’s energy transport infrastructure, by which natural gas from Russia transits into Western Europe, began sprouting in the media. It’s possible more people have seen the routes of these natgas pipelines than have seen the planned route of the Keystone XL pipeline across North America. Pipelines, we’re told, are power.

Geopolitics-by-pipe, as depicted by the Finland’s YLE.

Then we have unexpected events such as the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines flight 370, missing for over two weeks and now declared lost. Out of nowhere, the world’s eyes fixed on the fate of what would normally be an unremarkable aircraft. As a proverbial needle in an expansive haystack, the search for MH370 and its 239 passengers and crew immediately focused in part on its data exhaust, illuminating how such vessels are tracked.

The public are generally aware of iconic black box flight recorders, but less so of systems like standard aircraft transponders and the ACARS system that reports data about the plane’s condition to airlines, but which we now know may also be heard by some satellites like Inmarsat. Other systems talk to the plane’s manufacturer if desired, and to engine builders. In short, an aircraft like a 777 is talking to, and being listened to, by far more entities than just an air traffic controller. An entire dispersed infrastructure is in place to see and hear vessels like MH370.

Real-time map of commercial shipping in the Mediterranean, from AIS Marine Traffic.

The search for MH370 has also illuminated infrastructures including viable runways in Southeast Asia for large aircraft, shipping lanes for cargo, satellite coverage fields, and more. It’s also revealing which countries have stronger and weaker relationships by indicating who is sharing assets with whom in the search for the lost flight.

Of course, such events also reveal other blind spots. Amateur searchers have come to the realization that Google Earth, in stark contrast to the assumed amount of data Google is believed to absorb and process, does not provide a realtime view of the world. There are also real blind spots, places in the world where, at least so far as we know, very little is observed in fine grain detail—such as at handoff points between tracking systems, or through small gaps in radar, for example. In other cases, satellites we think watch our every move can’t see at all.

An illustration of spot beams from EUTELSAT coverage.

We shouldn’t wait for black swans to have to reveal hidden or unseen infrastructure, like a dye stain on a laboratory slide. While each individual doesn’t need to carry around a directory of networks, electrical schematics, energy conduits, or a copy of Jane’s Defense Weekly, we increasingly rely on awareness of how systems and infrastructure work, lest it disappear into the black box. As I write this, companies big and small are wreathing the planet in unseen systems to make logistics seem like magic, to make all of our interactions effortless and smart, or the technology we use daily bow obsequiously to our every need. They are doing so in the name of cost, comfort or convenience—our convenience.

As my friend Georgina Voss has been asking lately with her research into global supply chains, “What do we ask for, and what do we really get?” What tools, relationships and trade-offs hide behind the things we demand to keep our daily lives running smoothly, and what is done for us or to us in our names? What are the costs, and where are the cracks and traps? As

Julian Oliver, Gordan Savičić and Danja Vasiliev put it in the Critical Engineering Manifesto, “The greater the dependence on a technology the greater the need to study and expose its inner workings, regardless of ownership or legal provision.”

Most of what we’ve found out so far about hidden and unseen infrastructure through the MH370 search isn’t nefarious. There isn’t a secret air tracking system that takes advantage of our ignorance—in fact, it is there to provide safety and security. As our systems and infrastructure talk and leave trails and breadcrumbs, they become “smarter,” which in many cases are very helpful to us when our own observations fail.

It’s when we switch off, and choose not to be curious, to have even a vague sense about the “what,” “where,” and “how” of the systems around us that these systems do cost us. Whether it’s a supply chain scam such as shipping food across vast oceans and back just to shave pennies off processing, or a financial cheat like moving biodiesel across borders to game the system, or passing an entire country’s medical records out the back door, if we look away and just whistle while the deed is done, we might as well not look at all. Black swans are just that because they only happen once. A once-in-a-generation leak, a mistake, an accident, or a catastrophe is too late to alert us as to how things really work.

Thoughts inspired and informed by talks from Georgina Voss, Dan Williams, and Paul Graham Raven.

Two container ships enter the Suez Canal, via Maersk.